Crime-Preventive Architecture and Sustainable Development

Crime prevention is not solely a matter of policing or surveillance. Research consistently demonstrates that perceived and actual safety is largely shaped by how cities, buildings and public spaces are planned and designed.

By Chris Butters and Vikki Johansen. Published 19th January 2026.

How Architects Design Sustainable, Safe and Low-Carbon Cities

CPTED provides architects and urban planners with a research-based framework for understanding how physical environments influence behaviour, social interaction and perceptions of safety. When integrated early in architectural and urban development processes, CPTED contributes to robust, inclusive and socially sustainable urban environments, where safety is embedded in the spatial structure rather than added as an afterthought.

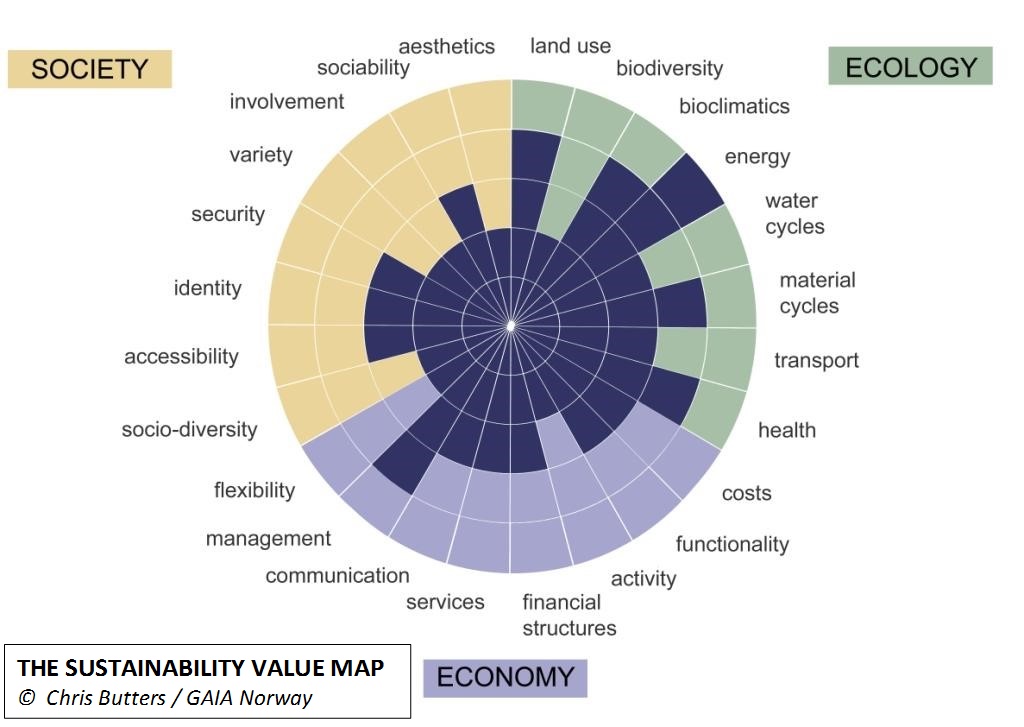

Chris Butters’ Value Map is a recognised decision-support tool that assists architects and developers throughout design, construction and post-occupancy phases, including building operation and evaluation (2):

What Is CPTED?

CPTED integrates architecture, urban planning and social sciences to reduce crime through design-led strategies, rather than control and reaction alone.

Core CPTED Principles:

- Natural surveillance – clear sightlines, active façades and windows overlooking streets and shared spaces

- Territorial reinforcement – clearly defined boundaries that signal ownership, responsibility and care

- Access control – managing movement between public, semi-private and private zones

- Activity support and maintenance – active, well-used and well-maintained spaces deter crime

Multiple studies document reduced crime rates and increased perceived safety in residential areas where CPTED principles are systematically applied (3,4).

Urban Form and Safety: High Density Without Losing Human Scale

Urban form plays a decisive role in both safety and sustainability. Experience from European cities shows that low-rise, high-density development, such as in Paris and Amsterdam, often delivers:

- Better daylight access in streets and courtyards

- Higher levels of natural surveillance

- More active ground floors and social interaction

- Strong conditions for green infrastructure and biodiversity

This urban form accommodates high population density without the social and environmental challenges that often arise when developments lose human scale.

Evidence-Based CPTED Outcomes

Research demonstrates clear links between design and safety:

- Residential burglary: Neighbourhoods applying CPTED principles show lower burglary rates (4)

- Public space: Case studies from cities such as London report reduced crime and improved perceived safety following CPTED interventions (1)

- Long-term effects: Integrating CPTED in planning delivers lasting social and public health benefits (3)

Practical CPTED Guidelines for Architects

- Maximise natural surveillance through orientation, window placement and active façades

- Define territory using planting, level changes and clear transitions between zones

- Control access without creating enclosed or unsafe spaces

- Support activity through mixed-use development and pedestrian-friendly design

- Prioritise maintenance and management – neglect and disorder undermine safety

- Ensure access to daylight and green spaces that support wellbeing, health and informal social control

Material Choices, Colour Psychology and Perceived Safety

Materials and colours strongly influence how spaces are perceived and used. Research in neuropsychology and environmental psychology shows that:

- Monotonous, hard materials can feel stressful and unsafe

- Earth tones and natural materials enhance comfort and social interaction

- Colour contrasts improve orientation, legibility and natural surveillance

- Calming colours in shared spaces can reduce stress and conflict levels (7–12)

Sustainability and Urban Form: The Need for Holistic Assessment

Sustainability cannot be evaluated in isolation. When assessments include:

- Embodied carbon

- Ground conditions and foundations

- Maintenance and life-cycle costs (LCC)

- Land use and biodiversity

- Social safety and wellbeing

research shows that urban form is a decisive factor in overall sustainability performance (5,6,15).

Low-rise, high-density development often provides:

- Lower material intensity

- Simpler structural systems

- Better conditions for green spaces and biodiversity

- Higher social quality and perceived safety

This typology can also be delivered in timber construction, achieving low carbon footprints alongside strong social performance—without many of the structural and environmental drawbacks associated with high-rise buildings.

Design Priorities for High-Rise Development

Where authorities have already decided to pursue high-rise development, architects and planners should prioritise human wellbeing and sustainability:

- Façades and materials: Textured façades, lighter colours and environmentally responsible materials can soften visual impact and improve social comfort

- Shared spaces: Use calming colours and natural elements in lifts, stairwells and corridors to reduce stress and conflict

- Daylight and green space: Ensure daylight reaches streets, courtyards and public areas; integrate green spaces that support activity and natural surveillance

- Social safety: Design circulation and public spaces to encourage encounters and social interaction

- Life-cycle perspective: Evaluate materials, maintenance and LCC to minimise long-term climate and resource impacts

These priorities help architects balance safety, wellbeing and sustainability, even in high-rise contexts, while safeguarding overall urban quality.

Conclusion: Safety and Sustainability Must Be Designed Together

By combining CPTED, material and colour psychology, and holistic life-cycle assessment, architects can:

- Strengthen social safety and quality of life

- Reduce crime through design

- Contribute to sustainable cities within planetary boundaries

Social sustainability can never be separated from climate, nature and resource use. Architecture that genuinely addresses sustainability must respect the planet’s limits for future generations.

“It is essential to maintain focus on climate and nature, even in times of increasing geopolitical uncertainty. Climate and environmental change remain among the greatest threats we face. This is also highlighted in the latest WEF Global Risk Report, even as short-term attention is drawn to political tensions and concerns about the negative impacts of AI technology.”

Thina Saltvedt, Chief Analyst Sustainable Finance, Nordea

References (Vancouver style)

- Armitage R, Monchuk L. Crime prevention in urban spaces through environmental design: A critical UK perspective. Cities. 2019;92:102–109. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0264275118317153

- Butters C. The Value Map for Sustainable Development.

- MDPI. A social-ecological resilience assessment and governance guide for urbanisation processes in East China. Sustainability. 2016;8(11):1101. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/8/11/1101

- Cozens PM, Neale R, Whitaker J, Hillier D. Examining the effects of CPTED on residential burglary. Sustainability. 2016;8(11):1101. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1756061616300490

- Ma L, Azari R, Elnimeiri M. BIM-based life cycle assessment of embodied carbon in high-rise structures. Sustainability. 2024;16(2):569. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/16/2/569

- Stockholm Resilience Centre. Planetary boundaries. Available from: https://www.stockholmresilience.org/research/planetary-boundaries.html

- Alexander GS, Schauss AG. The physiological effect of colour on the suppression of human aggression. 1980. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236843504

- Young S, Gibson R. Does Baker-Miller pink reduce aggression? 2015. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279745276

- Hosseini SM, Pourghasem H, Jafari S. What’s in a colour? Neuropsychologia. 2022;170:108173. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0911604422000276

- Nature Research. Colour psychology and perception. Available from: https://www.nature.com/research-intelligence/nri-topic-summaries/color-psychology-and-perception-micro-33279

- Xiao Y, Wang Q, Li J, et al. Differential colour tuning of the mesolimbic reward system. Sci Rep. 2020;10:10815. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-66574-w

- Cambridge University Press. The neuropsychology of colour. 2020. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/color-categories-in-thought-and-language/neuropsychology-of-color/E299C19C2BE7EF6FA2D30D5B8702EC4A

- Butters C, Cheshmehzangi A, Sassi P. Cities, Energy and Climate: Seven Reasons to Question the Dense High-Rise City. Journal of Green Building. 2020;15:197–214. https://doi.org/10.3992/jgb.15.3.197

Also read: Sustainable Investments Outperformed Traditional Funds in 2025